The 2024 Levels Guide to metabolic health and aging

Discover what you can do to live longer and make those years healthier, more productive, and enjoyable.

Aging is an inevitable fact of life. As time passes, biology takes its course, and most people grow and decline in predictable ways. But questions remain when it comes to both lifespan and quality of life. Why do some people die in their 50s or 60s while others live past 100? How do some seem 20 years younger than their biological age while others appear decades older? These questions suggest that certain factors help people live and stay in better health for longer.

The answers may lie, in large part, with our metabolic health. This set of cellular mechanisms generates energy from our food and environment to power every cell in our body. When these pathways run smoothly, we have optimal metabolic health. When they don’t, the conditions for a disease state sets in. It’s no accident that there are links between blood sugar dysregulation and eight of the top ten leading pre-Covid causes of death in the United States, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and kidney disease.

Metabolic health plays a role in the two main components of longevity: our chronological lifespan and our healthspan, or the quality of our years. When we enhance our metabolic health, we not only live longer, we live healthier.

What factors contribute to aging and eventual death?

Scientifically, aging is the deterioration of the physiological functions you need to survive over time. At any point in life, disease, injury, and other stressors may harm our cells. When we’re younger, these damaged cells are removed by our immune systems. But as we get older, our bodies can’t do this as well.

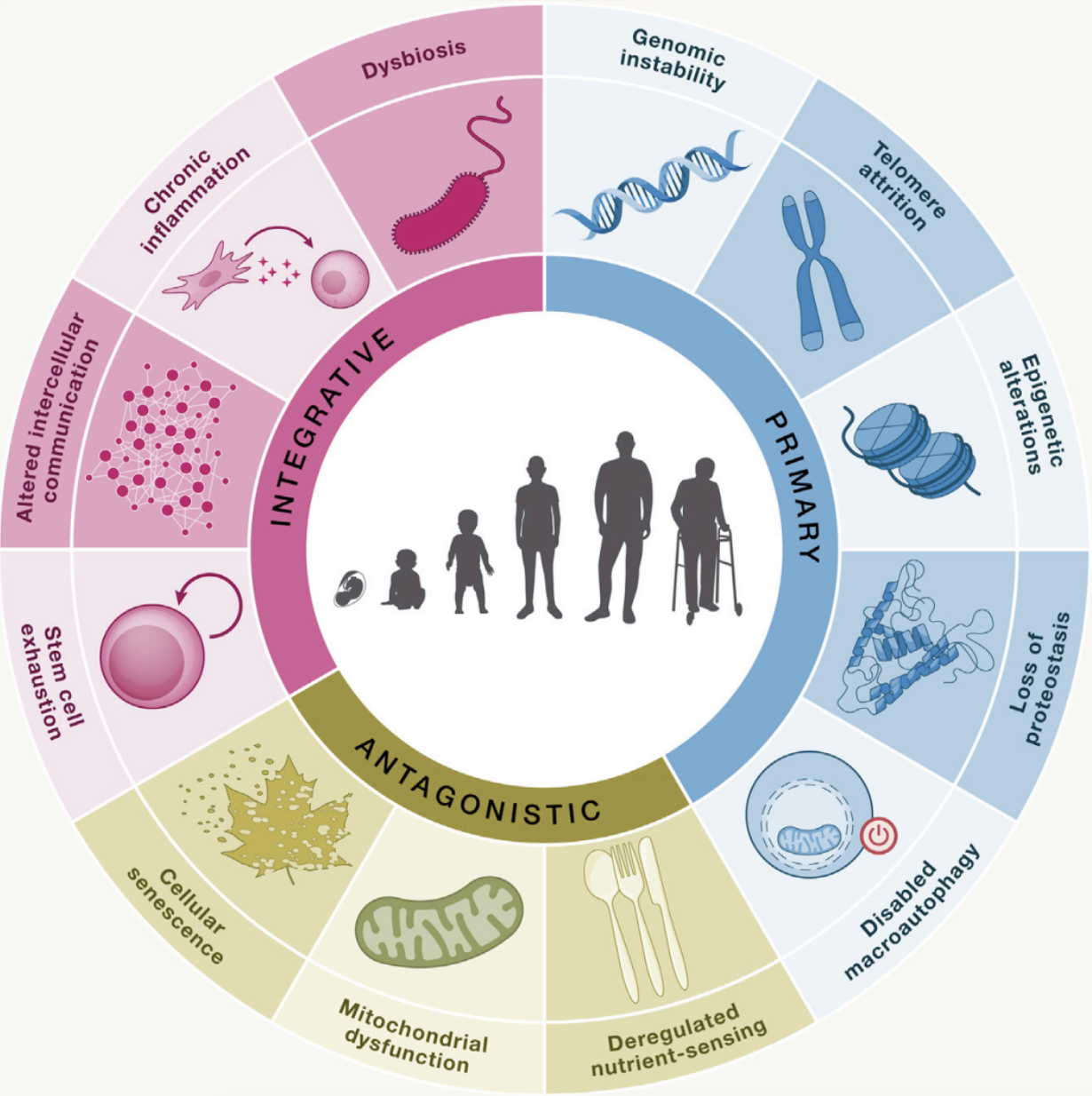

A landmark 2023 paper described 12 cellular hallmarks of aging [see image below], which include several mechanisms related to metabolic health.

Mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are the energy-producing organelles in our cells. Their function naturally degrades with age due to several processes in the cells, but some treatments that support mitochondrial health by reducing inflammation or oxidative stress may improve lifespan in animal models.

Dysregulated nutrient sensing. The way your body senses and responds to the presence or absence of nutrients is highly complex, involving dozens of chemicals and pathways, including rapamycin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF1). This network of sensors and communication regulates nearly all cellular activity. When your body thinks it is nutrient deficient (starving), it can trigger cell defenses like autophagy or DNA repair. This is one way diet connects directly to longevity and why some evidence suggests dietary strategies like intermittent fasting and ketosis may improve lifespan.

Chronic inflammation. Increased inflammation is a natural consequence of aging, both on its own and as a downstream effect of several other hallmarks, such as DNA breakdown and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Cellular senescence. Cellular senescence is a process where cells no longer multiply, but they don’t die off when they’re damaged either. Senescent cells have some benefits, including wound healing and tissue repair. But they also promote age-related tissue dysfunction and contribute to the development and progression of Type 2 diabetes and other diseases (such as osteoarthritis and heart disease) because they release chemicals such as cytokines that trigger inflammation. That inflammation can spread to other cells, where it causes further damage.

Changes in DNA. Telomeres, the caps at the end of chromosomes, shorten with age. As a result, the DNA becomes exposed at the chromosome’s end. When our cells detect this, they think the DNA has broken off and try to make a repair. They may fuse two ends of different chromosomes, which can lead to cancerous cells forming. As a safer alternative, cells with telomeres that are too short may undergo senescence. As such, shorter telomeres are associated with several conditions, including lung diseases, blood cell disorders, metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, bone diseases, kidney disease, and neurodegenerative diseases.

The connection between metabolic health and longevity

A lot of research shows that metabolic health declines with age. For example, aging is associated with decreased glucose tolerance and an increased risk of insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. It’s not clear why this is. Some speculate this is due to the overexpression of a particular enzyme, MT1-MMP, a central regulator of insulin sensitivity during aging, while others think it might be due to changes in the enzyme PTP1B, which is involved in insulin receptor desensitization and other factors.

Additionally, while the decline in glucose metabolism from ages 17-59 can often be explained by changes in body composition and physical fitness, the decline for older ages appears to involve other factors as well.

For one, as we age, we see a decline in the energy output of our mitochondria, the cellular components that generate energy to power our cells. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of many diseases of aging, and hyperglycemia can accelerate these changes. This can lead to all sorts of problems, including degenerative brain diseases and depression, among other conditions.

In addition, body fat typically increases, especially in our midsection, with age. This is partly due to hormonal changes such as menopause but is also largely influenced by loss of muscle mass, which slows down our resting metabolic rate. Excess visceral fat (which surrounds organs) can contribute to insulin resistance.

Chronic disease is another link between metabolic health and aging. The odds are overwhelming that most of us will die as a result of one of the chronic diseases of aging–heart disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease, and Type 2 diabetes–which longevity expert Peter Attia calls the “four horsemen” in his book Outlive.. It’s important to understand our personal risk factors and be proactive in managing them. When it gets to the point that we need to treat the disease, in many cases, it’s too late.

Take diabetes. Prediabetes is underdiagnosed, and when it is diagnosed, people are often given vague directions on lifestyle modifications and blood sugar management. The medical establishment frequently doesn’t intervene until full-blown diabetes is present, at which time medications are prescribed, and it’s harder to reverse.

Still, metabolic health is largely under your control. While cellular energy metabolism naturally changes with age, full-blown metabolic disease is often avoidable. Metabolic dysfunction is compounded by poor nutrition, too little exercise, chronic sleep loss and stress, and the resulting health implications.

Metabolic health is defined by optimal levels of five markers: blood sugar levels, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, blood pressure, and waist circumference, without medication use. This means:

-

A waistline less than 35 inches for women and 40 inches for men.

-

Fasting glucose below 100 mg/dL

-

HDL cholesterol above 40 mg/dL (men) or 50 mg/dL (women)

-

Triglycerides below 150 mg/dL

-

Blood pressure of 130/85 or less

Ninety-three percent of American adults have sub-optimal metabolic health, as measured by similar markers. About one in three American adults has at least three of these markers out of range, a condition known as metabolic syndrome.

How to improve metabolic health to age better

Just like we can get into better physical shape, we can improve our metabolic health. As a bonus, by making intelligent daily choices about diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management, we also improve longevity. Here are some essential steps you can take:

Exercise

Exercise supports longevity for obvious reasons: improved blood flow, lung strength, and heart health. And it also impacts us on a cellular scale. People who exercise regularly have longer telomeres. One study found that highly active adults, such as those who jog for a half hour five days per week, have telomeres that appear to be nearly a decade younger than those who live more sedentary lives. According to Harvard biologist and Levels advisor David Sinclair, longevity expert, in his book Lifespan, “Many of the longevity genes that are turned on by exercise are responsible for the health benefits of exercise, such as extending telomeres, growing new microvessels that deliver oxygen to cells, and boosting the activity of mitochondria, which burn oxygen to make chemical energy.” Any exercise has benefits, but fasted cardio, Zone 2 training, and strength training provide unique benefits by increasing muscle mass, which helps glucose uptake and protects against injury, as well as increasing metabolic flexibility.

Limit added sugars and refined carbohydrates

Many different eating styles support metabolic health. The most important characteristics of these diets are they provide a wide range of nutrients, are minimally processed, and are low in sugar. Limiting refined carbohydrates and added sugars is particularly important to maintain stable blood sugar and ward off the risk of prediabetes and other metabolic conditions. Research shows that diets high in added sugars both directly and indirectly promote the development of metabolic diseases due to dysregulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and increased body fat.

Eat less often

Research suggests time-restricted feeding, where you eat only within a specific time window, can reduce inflammation and may improve cardiovascular health and fend off obesity. One way to do this is to follow a 16:8 diet (eating only in an eight-hour window each day) or eat 75 percent fewer calories two days a week (the 5:2 diet).

Don’t smoke

The DNA damage that happens from smoking ages us well before our time. Secondhand smoke is dangerous, too. Vaping also appears to cause DNA damage, as does high-dose THC marijuana use.

Get seven to eight hours of sleep a night

That seems to be the sweet spot—less than six hours or more than nine appears to increase risk of death from conditions such as heart disease, stroke, or cancer. One small study of healthy young men forced to get just 4 hours of sleep a night found that after four days, they had elevated insulin levels similar to that of older adults with impaired glucose response.

Undergo advanced metabolic blood testing

Most of us get a standard panel of blood tests like cholesterol and glucose every year at our annual physical. But there are more nuanced tests to get, too. Cholesterol levels alone, for example, don’t paint a complete picture. Recent studies show that measuring Apolipoprotein B-100 (ApoB), a protein attached to disease-causing cholesterol particles in your bloodstream, is a better indicator of heart disease risk than other tests. However, this is not part of a standard metabolic blood panel. Fasting insulin is another valuable indicator of metabolic health that’s rarely tested. Elevated fasting insulin is a precursor to insulin resistance, and this can be identified and addressed years before metabolic disease develops.

Experiment with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM)

A CGM provides your real-time blood sugar response to foods, exercise, sleep, and more. This can help you monitor your glycemic variability and average daily glucose levels, which may be better than an annual fasting glucose test. Once you have a sense of what blood glucose levels are normal versus optimal for you, you can make changes to proactively manage anything that’s suboptimal before it develops into disease.

Get a better view of your metabolic health

The best way to understand how well your body processes your diet and lifestyle choices is with a continuous glucose monitor and an app like Levels to help you interpret the data. Levels members get access to the most advanced CGMs and personalized guidance to build healthy, sustainable habits. Click here to learn more about Levels.