Sam Corcos is the co-founder and CEO of Levels, a biowearable company that shows you how food affects your health using real-time biological data. Prior to founding Levels, he was the founder of CarDash (YC’17).

People often wonder how startup CEOs spend their time. Well, I’m a bit obsessive, and I track every 15-minute increment of how I spend my time and I’ve been doing so religiously for years. A little background — as a four-time founder, I've historically been on the technical side of the companies, either as an individual contributor or leading engineering teams. My role as CEO of Levels is my first non-technical role.

I started tracking my time more seriously after I installed an app and, to my horror, discovered that I was spending more than three hours per day on social media and several additional hours consuming news. This was especially surprising because if you had asked me how much time I was spending on these things, I would have guessed probably 20 minutes a day. It nudged me to make some serious changes with how I spent my time.

Being intentional about time management has also forced me to be realistic about how much I could actually accomplish in a given time period. There are seemingly endless demands on your time as a founder-CEO. I’ve found that by tracking my time rigorously, I’m constantly taking the pulse if I’m spending the appropriate amount of time on the areas most critical for the business.

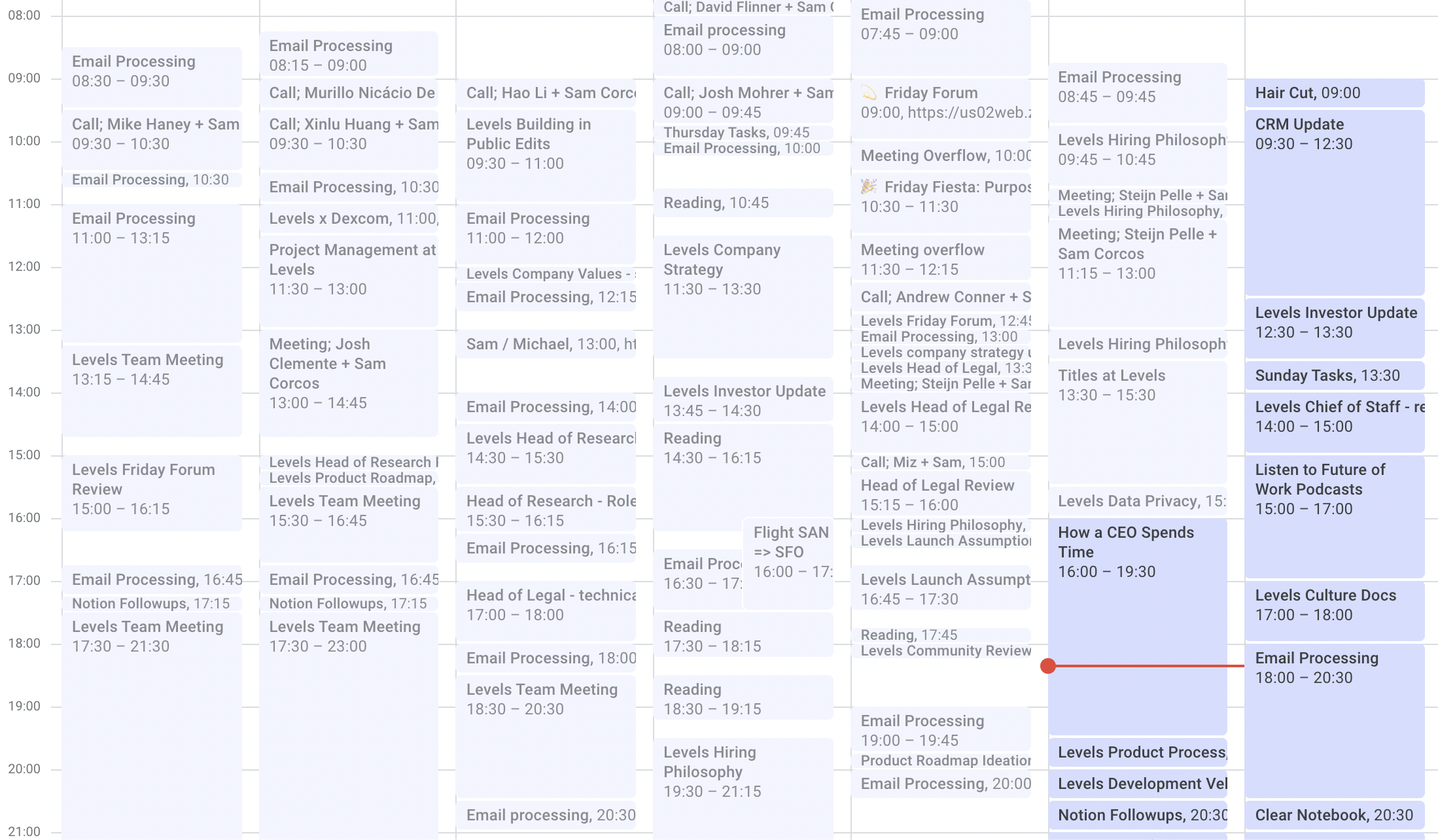

So in the spirit of the two-year anniversary of the founding of Levels, I thought I’d share a little about how I spent my time for the first two years, backed up with data. My goal? For folks out there with hopes to become a startup CEO, you can get a behind-the-scenes deep dive into how you might actually spend your time on the path to building a company. This article isn’t an optimistic or sanitized take on how I’d like to spend my time; it’s an unvarnished look at how I actually spent my time over the last two years. For example, here’s what my calendar looks like right now as I’m writing this.

When you sign up for the role of CEO at a startup, you should know what you’re getting yourself into. Most of the time, it’s an all-consuming job, though some people are able to do it while maintaining more “life” in their work-life balance. The goal of this piece isn’t to glorify working to the point of burnout — but don’t expect it to be a normal desk job.

In this article, I unpack some of my biggest surprises from deeply analyzing the data — and what it says about the ever-changing role of a startup CEO. I walk through some of the common traps I see other CEOs fall into that are stifling their impact and company growth. I’ll also give an in-depth view of how I specifically spent my time in each area of the business, and how this shifted across each phase of the journey building Levels. Along the way, I’ll provide plenty of tested tactics for implementing your own system for optimizing your time as a CEO. Let’s dive in.

THE ART OF WEARING MANY HATS AS CEO

Before we dive into the data, a few observations. Probably my biggest surprise looking at how I spent my first two years was how variable the role of a CEO is at different points in the company’s history. One thing that's clear from the data: CEOs wear many hats.

What I spent my time on oscillated as the needs of the company changed, and I had to be ready to switch gears at any time. There were some months when I took on meaningful engineering responsibilities, others where I was primarily a salesman, and others when I was taking lead on fundraising. These constantly shifting priorities and deliverables can make it difficult to know if you’re allocating your time correctly.

Unblocking others is your top priority

But regardless of whether you’re focused on fundraising, selling, or product, as a CEO you’re responsible for the output of the entire organization. In my current role at the company, I think of myself as an information router, so my primary job is to unblock everyone else on the team to operate at peak efficiency.

If the company is a steam engine, my job is to be the lubricant — I don’t have any real deliverables other than to make sure all the other parts are running smoothly.

If I find out that the Engineering team is blocked by data integrity issues, or that the Growth team is confused due to a lack of clear company strategy, or that the Product team is being slowed down by a lack of process, it’s my job to step in and support where needed.

It’s not uncommon for me to uncover something in a conversation that’s slowing the company down (e.g. the Operations team is spending far too much time manually reconciling orders), which then leads me to block off a substantial chunk of the following week to solve the problem.

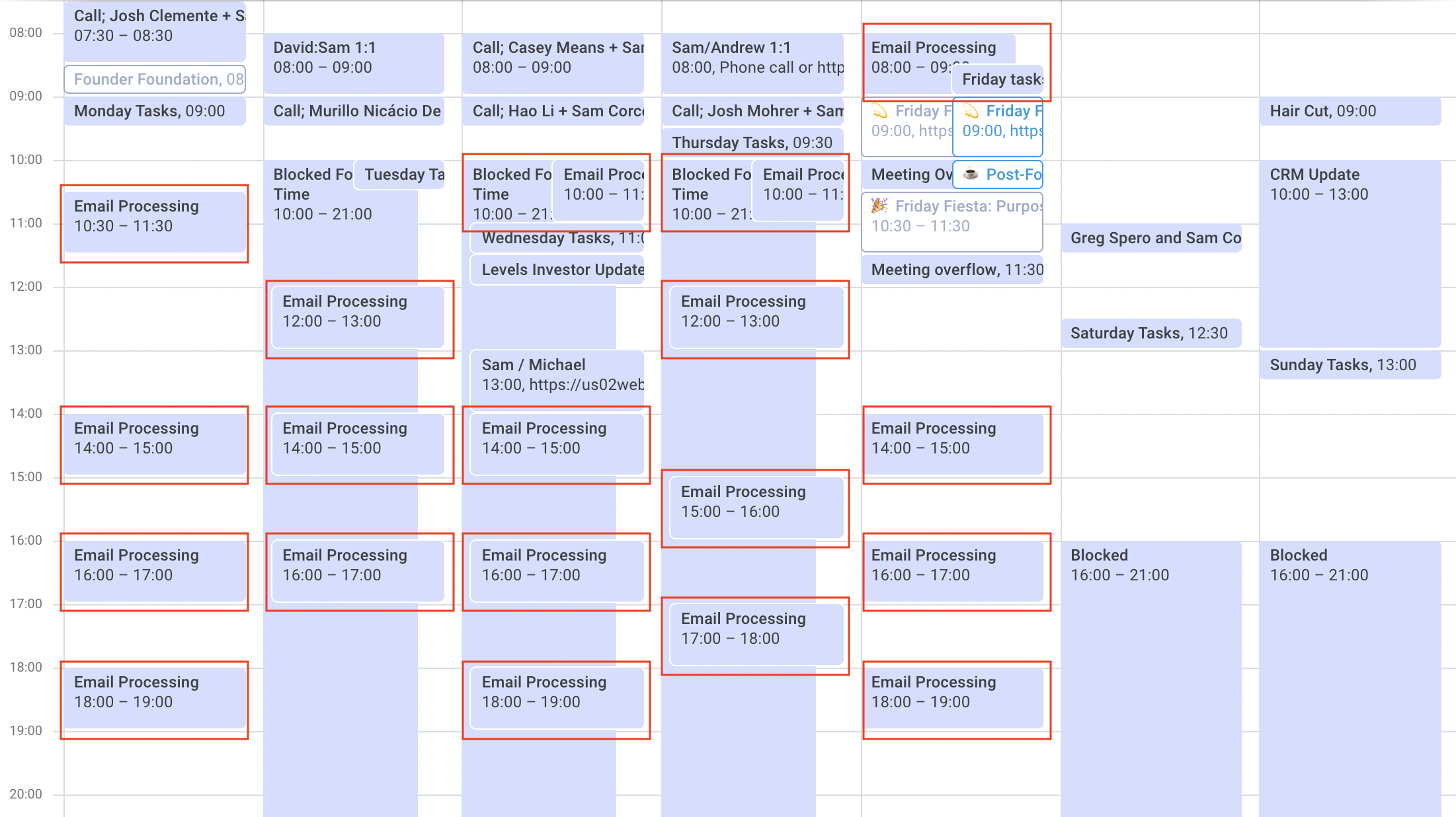

- Takeaway #1: You should primarily be an information router, and you need to make communication a top priority. Block off recurring blocks of time every day to process email. I know that I need to process 3-4 hours of email every day in order to stay on top of communication, so adding these blocks to my calendar forces me to stay realistic about how much other work I can actually do in a given week (see screenshot below of my calendar five weeks from now). Don’t treat communications as an afterthought. It’s your main job.

- Takeaway #2: Make sure you keep bandwidth open and always seek to make yourself redundant. It’s only during times when you have the available capacity that you can see where the gaps are in the company. If you’re too focused on your own deliverables, you’re at risk of missing the forest for the trees. A specific tactical piece of advice would be if you find that you regularly have action items and deliverables assigned to you, you should try to find a way to hand those off to other people. It either means you don’t trust your team enough to delegate projects to them or you need to hire someone with the skillset needed to execute against those deliverables.

Ditch your to-do list

Being a master at time management should be one of your core competencies. You’re going to have a lot of balls in the air and you need to make sure you don’t drop them — or at the very least, ensure that they don’t drop silently. Here are a few of the principles of time management that I’ve learned.

The most substantial improvement in my ability to manage my time came from using my calendar as my to-do list (and subsequently killing my to-do list). Killing my to-do list has also had the unintended consequence of substantially reducing my personal stress and anxiety — it’s been one of my biggest mental health wins of all time.

The problem with to-do lists is they lead to unrealistic optimism about how much you can accomplish because items on a to-do list are untethered from the constraint of reality: time.

I used to have the habit of overcommitting myself, which became a major source of anxiety in my life because I was dropping balls left and right, and it led me to disappoint a lot of people when deadlines would slip. Tactically, the way this works now is that if someone asks me to do something or if I have a task that needs to be completed, I go to my calendar and block off time for that task.

When people ask me now, “Can you have this done by Friday?” I can easily look at my calendar and respond, “I have exactly two hours open this week, so if it’s going to take more than two hours, we’ll have to change my priorities or I won’t get it done until next week.” Having this level of clarity on my time has been a huge win.

I’ve also found that using a calendar in this way helps surface my priorities. My calendar is often filled a week or two in advance, and being able to take a step back and see what I’ll get done next week allows me to ask myself, “Are these things really the highest and best use of my time?” The answer is often no, which leads me to hand things off to someone else on the team who is better suited to solve the problem or kill the project entirely. It’s a useful forcing function.

Another bonus is that using your calendar as a to-do list makes it easier to close the loop and give folks status updates. For example, imagine you've committed to completing something by Tuesday (and add it to your calendar), but something comes up and you're no longer able to finish it by the due date. With the calendar as your to-do list, you're forced to move that action item to a different day, and it serves as a reminder to reach out to the stakeholder who is expecting it to be done Tuesday to let them know you're running behind.

- Takeaway: Kill your to-do list and use your calendar as your to-do list instead. If you take one action item from this piece, it should be this one.

Don’t let recency determine priority

I advise a number of early-stage companies, many of which are run by first-time founders. One of the most common issues I see related to time management is that they have a set of important tasks that constantly get interrupted by seemingly urgent tasks that come into their inbox. It’s important to keep a clear focus on what moves the ball forward for your company and not let shiny objects distract you.

Your job as a CEO is to build fire departments, not put out fires. If you’re regularly putting out fires yourself, you’re doing it wrong. Focus your time on how to enable others on your team to put out fires themselves.

If you find yourself constantly pulled in different directions, you should reflect on why that’s happening and make some changes. If it’s because you don’t have someone on your team that you can trust with solving these problems independently (like a Head of Operations), then you need to hire for that role immediately. If it’s because you have a hard time distinguishing between urgent and non-urgent problems, I’ve found that asking myself the following question tends to clarify things: If in a year we looked back on this decision, is this the decision that killed the company?

The answer is usually no. Startups are default dead, so you have to ruthlessly prioritize the things that get you to default alive. That’s the CEO’s job.

- Takeaway: It’s possible that the communication tools you’re using are contributing to this problem. Text messages and Slack in particular can be highly disruptive because if you don’t take the action in the message immediately upon receipt, it’ll most likely get lost in the information firehose (unlike email, which is easier to triage). I recommend using asynchronous tools like email as your primary means of communication and turn off notifications for Slack and other disruptive tools. If someone really needs to get a hold of you, they can call you. I can tell you from experience, this rarely happens in practice — most things are not actually urgent. One great tool that helps with this problem for email is Mailman, which lets you batch and set delivery times for email — meaning, I only receive email in batches twice a day (2pm and 6pm). This tool helps me stay focused and it’s cured me of the habit of compulsively checking email like it’s a slot machine.

THE EXACT CATEGORIES I USE TO TRACK MY TIME

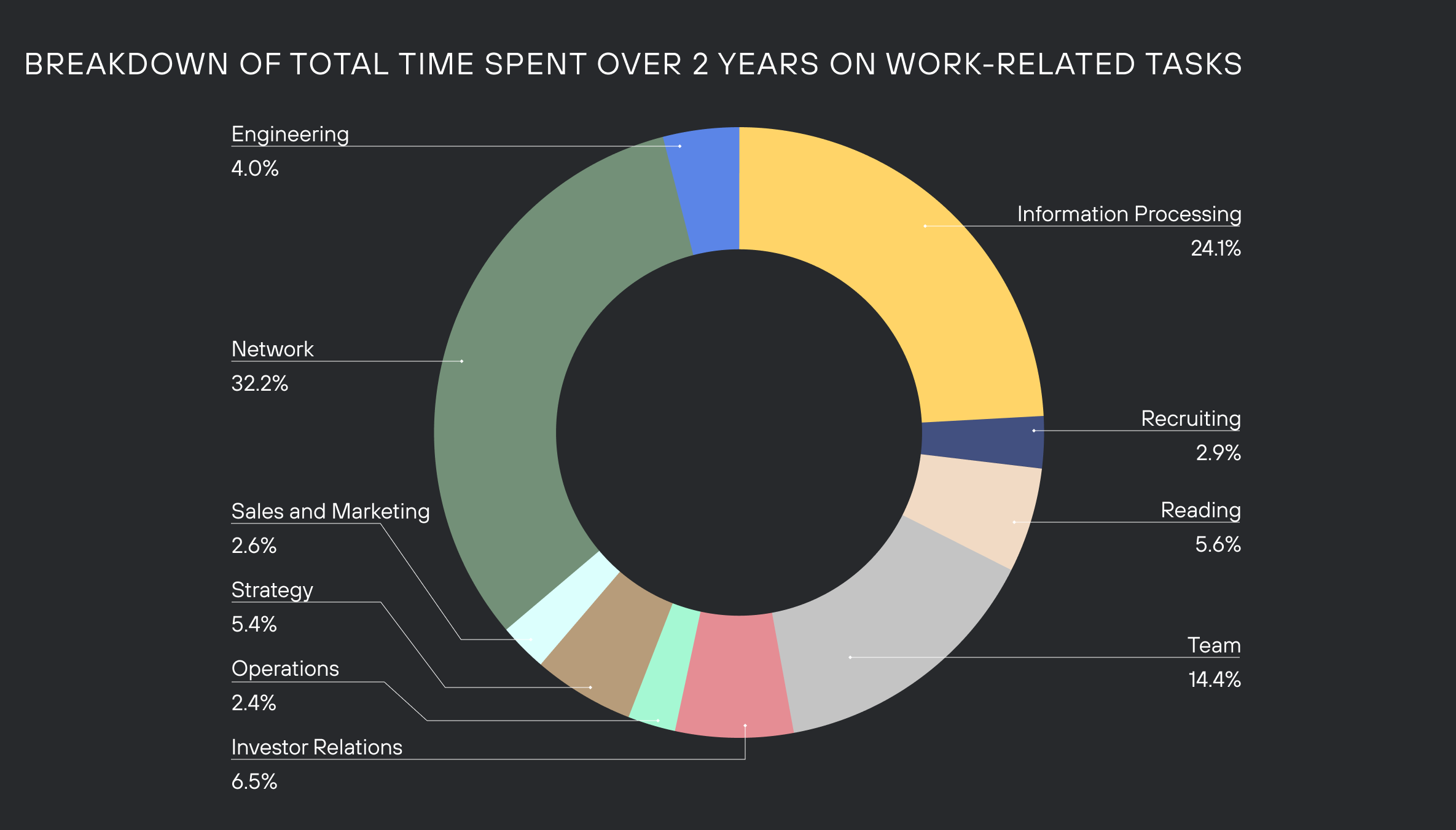

In order to do this analysis, I create categories that each action I took would fit into. I kept the number of categories limited to 10, and I’ve included the definitions of each of these categories below for clarity. Anything that didn’t fit neatly into one of the existing categories was lumped into Operations.

Depending on the responsibilities you have within your company, there’s a good chance you’ll end up with a list that’s different from mine. My only recommendation is to limit the number of categories to no more than 10 — otherwise, things get out of hand pretty quickly.

- Information Processing: Includes email processing, text message processing, Slack, and other forms of communication. But it’s mostly email.

- Recruiting: Team building, interviewing, or other things done with the intent of adding people to the team.

- Reading: Time spent reading books. I aim to read 100 books per year — as Bismark said, “Fools learn from experience. I prefer to learn from the experience of others.”

- Team: Any time spent with another person who is working on something Levels-related. This mostly includes 1:1s and calls with people who work with Levels.

- Investor Relations: Time spent interacting with existing investors, preparing for something fundraising-related, or talking to people with the intent of raising money.

- Strategy: Thinking about long-term company objectives and writing about concepts and principles for the company.

- Sales and Marketing: Directly selling Levels to people and doing user research for marketing purposes.

- Network: Connecting with folks that are work-adjacent, or potentially work-adjacent, for which the intent of the call does not fit into Recruiting or Investor Relations.

- Engineering: Time spent building stuff. Also includes time spent working on Product, but in my case, it was mostly engineering.

- Operations: Time spent working with the operations team, doing legal paperwork, taxes, HR, and other catch-all tasks that don’t fit neatly into other categories.

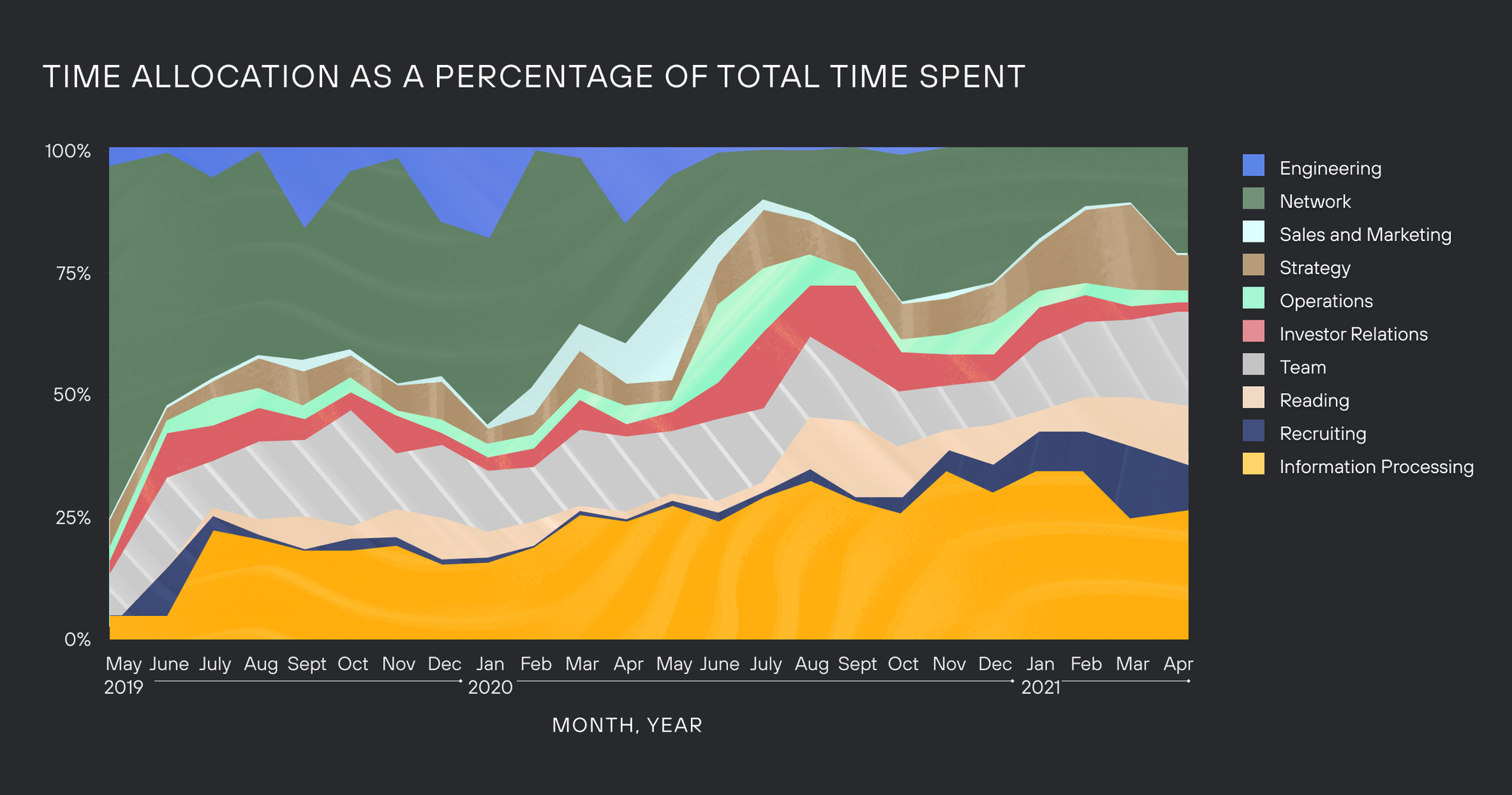

With that in mind, here’s a breakdown of total time spent over two years on work-related tasks:

TIME SPENT AS CEO: EXPECTATIONS VS. REALITY

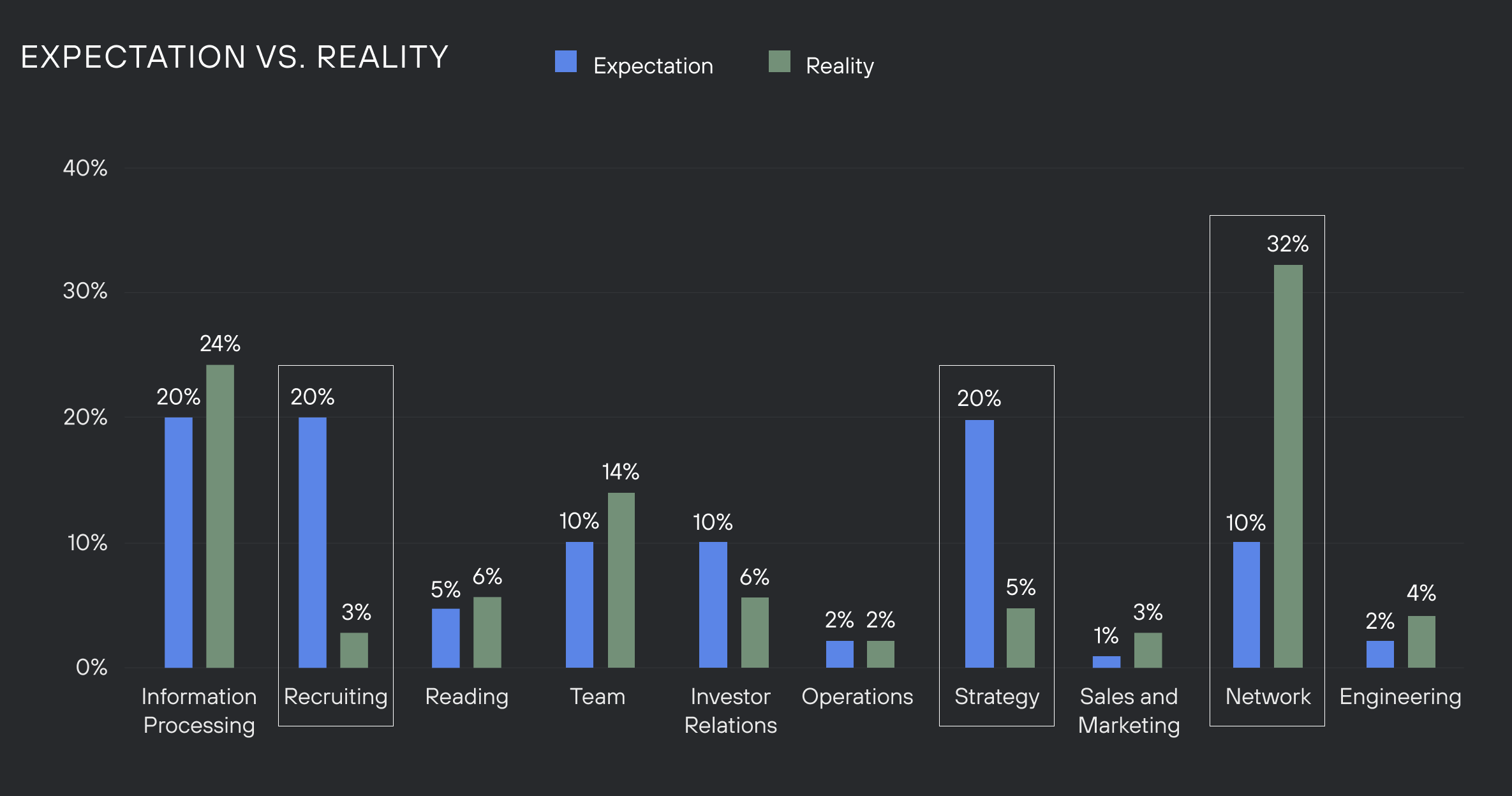

One of the most interesting things that came out of this exercise was how different my actual time spent was from my expectations. For a direct comparison, this is how my expectations stacked up to reality:

Specifically, I spent a lot less time on recruiting and strategy than I expected, and a lot more time on network than I anticipated.

I had to reflect on this for a while. As anyone on the inside knows, we spend a lot of time writing documentation and strategy. I’ve personally written several hundred pages of internal company strategy, and yet, it was only 5% of my total time allocation. I think the lesson from this is that not all work has the same emotional impact.

Work that is fun, easy, or energizing feels like it takes up less time, while work that is demanding or emotionally taxing feels like it takes up more time than it actually did.

When it comes to writing (which encapsulates most of the strategy category), I find that I have to be in the right mental state to do it effectively, and while writing a memo might only take 30-60 minutes, it usually feels like it took much longer.

More than most things, recruiting gives me anxiety. Searching for people, getting rejected constantly, and awkwardly trying to get introductions to potential candidates is not fun. I expected that I was spending about 20% of my time on recruiting, but the reality is that I only spent about 3% of my time on it.

- Takeaway #1: Be mindful that the way you’re actually spending your time might be different than your expectation. You may need to reprioritize. In our case, I’ve often worried that we spend too much time thinking about strategy and writing documentation. As anyone who has seen our strategy documents will tell you, they’re extremely comprehensive. But upon realizing that it’s only 5% of my time, it made me realize that we may actually be under-investing in strategy.

- Takeaway #2: Sometimes it can feel like a particular task — like writing a strategy memo — is going to take me hours, or even days, so I’ll often put it off and feel anxiety about completing it. Knowing (with data) that the actual time spent on that task will be relatively low helps me approach the work with a better frame of mind — in other words, reducing the emotional cost.

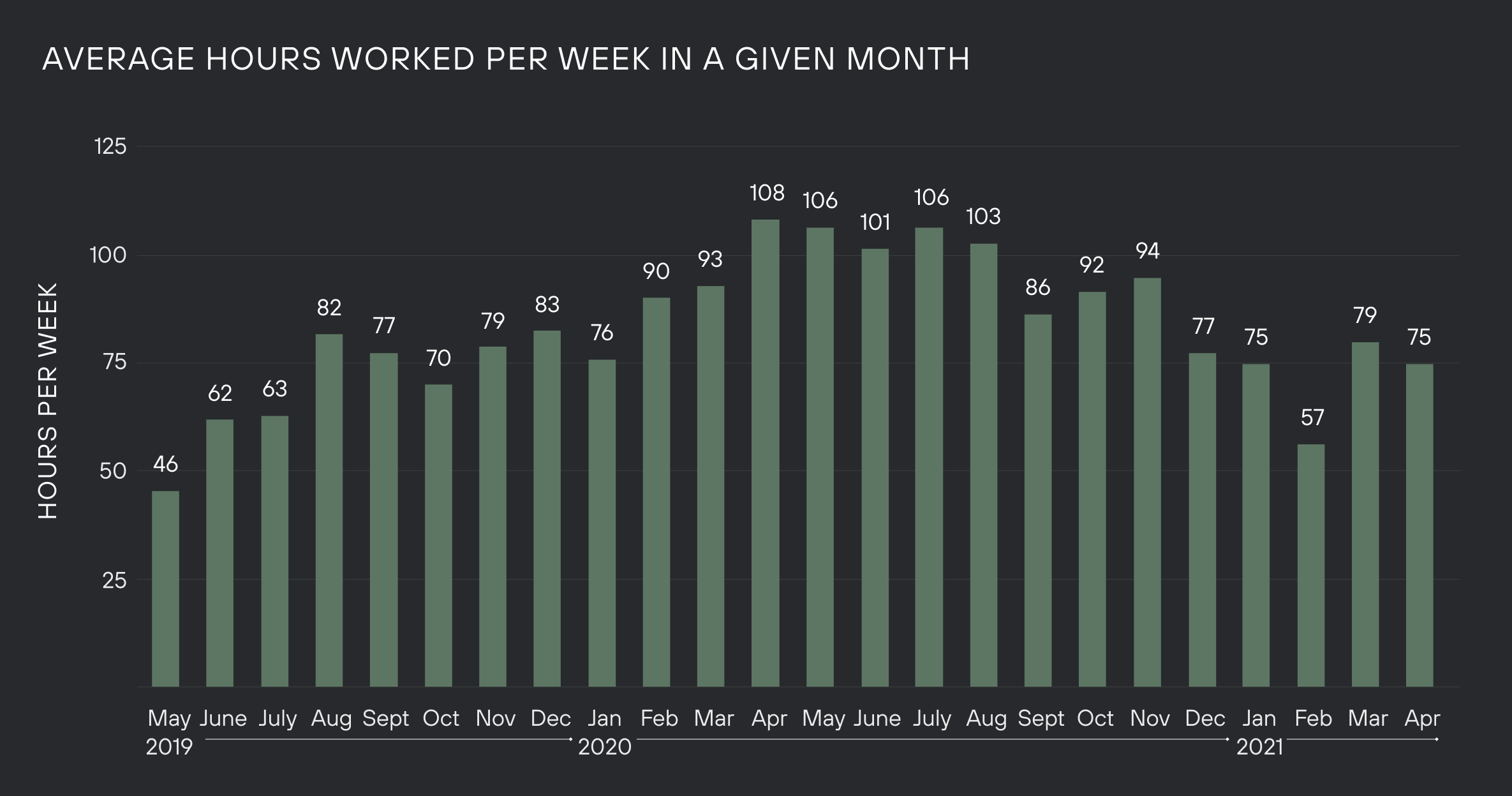

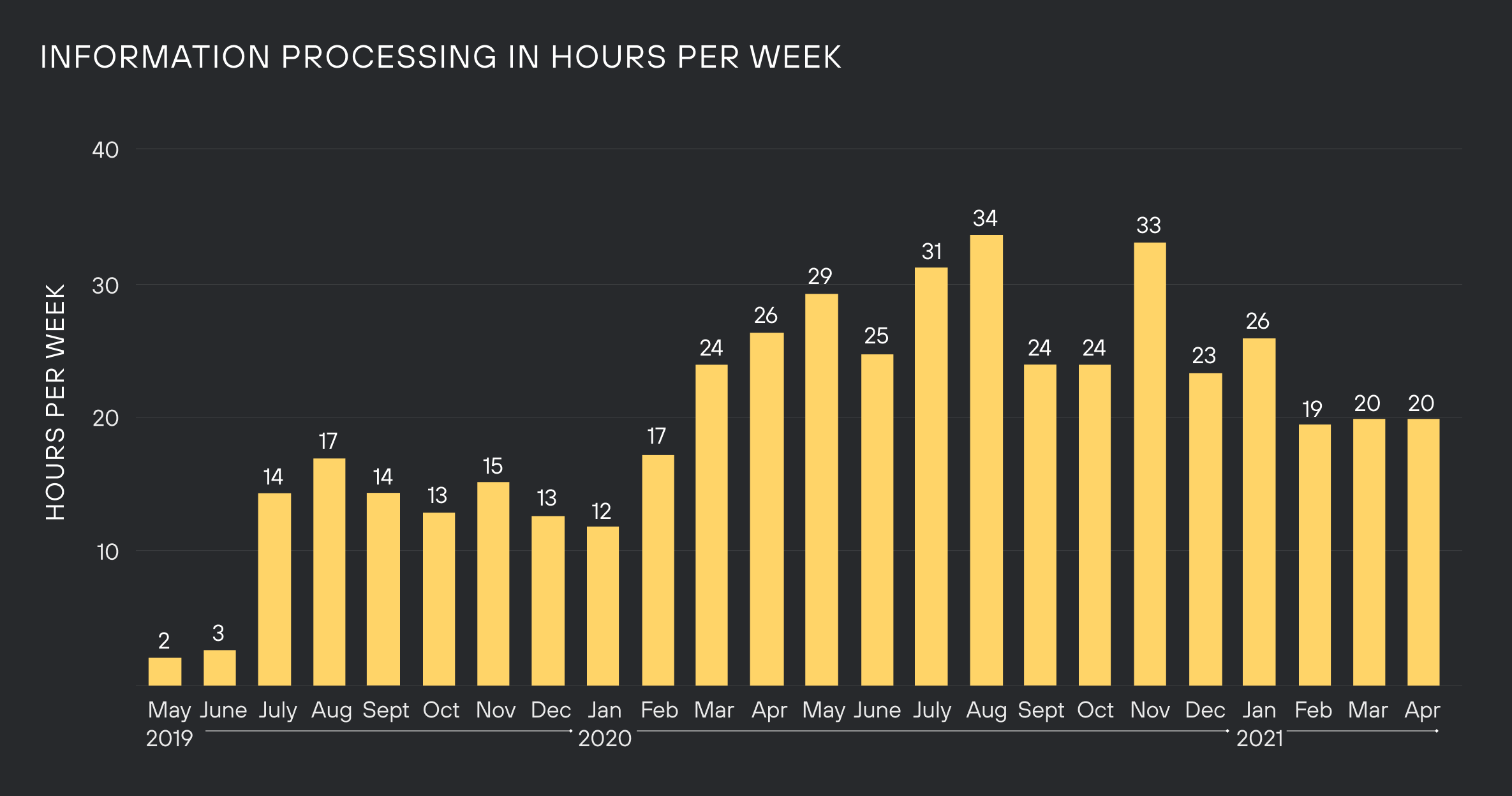

An unvarnished look at hours spent

I put a lot of hours into Levels over the last two years — 7,922 hours to be precise — and those hours were spread across a wide range of ever-changing responsibilities. Not only that, but both the number of hours spent and the primary responsibilities changed from month to month as the needs of the company changed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the number of hours spent on Levels was at its peak during our seed fundraise in late summer 2020. As the CEO of a venture-backed startup, you have to know what you’re signing up for. It’s a lot of hours and there isn’t much time for anything else. It’s not reasonable to expect everyone else at your company to live the same lifestyle.

Now, let’s dive deeper into each category.

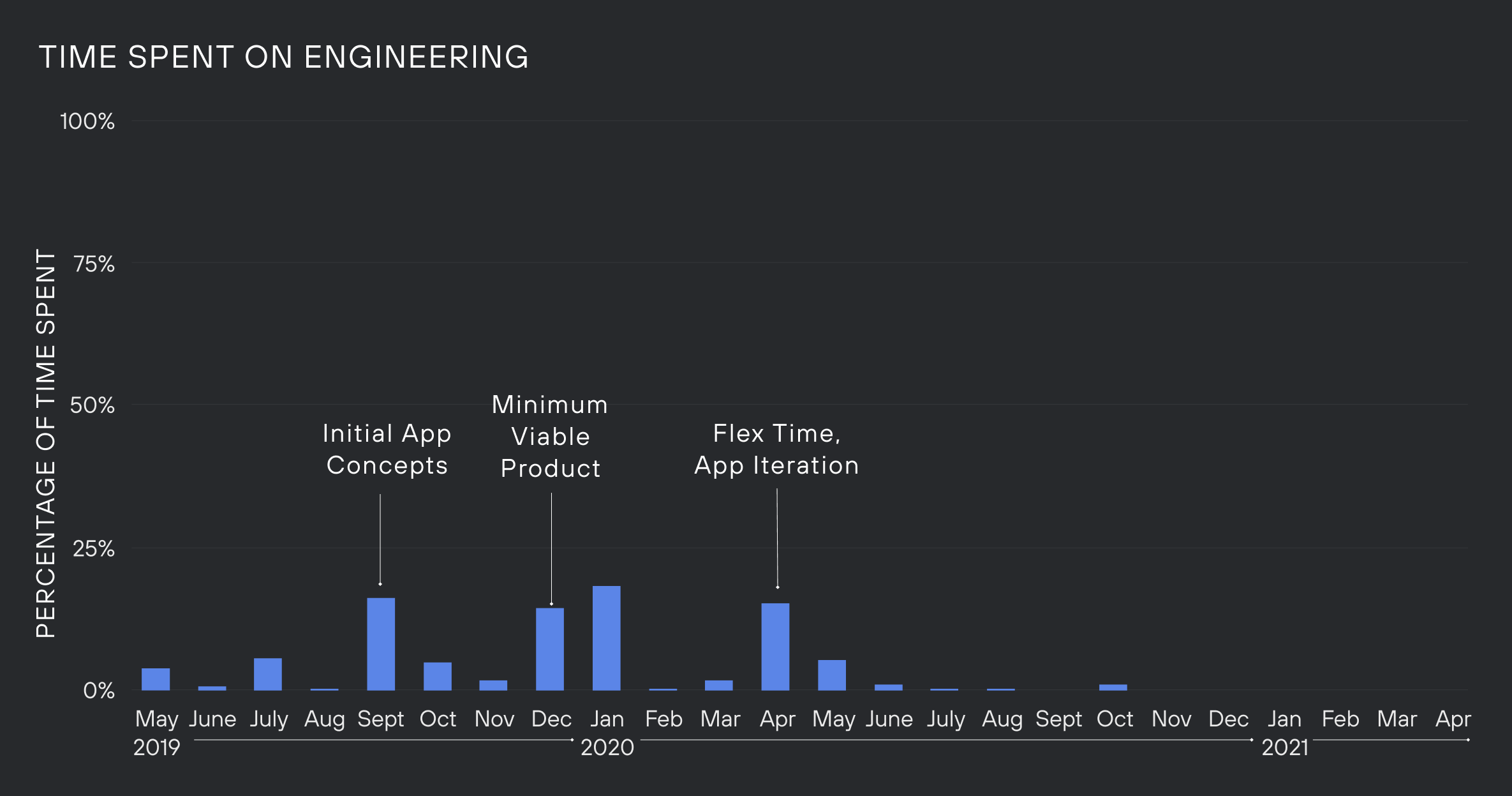

Engineering

There were three distinct periods in the first two years of the company when I was deeply involved in engineering. For the first two periods, contributing to engineering was the highest and best use of my time, as we needed to get something shipped as soon as possible. In the third period, it was largely because I didn’t have anything better to do (more on this below).

The first period was early on in the company’s history, mostly doing conceptual work and thinking through basic architecture decisions with the rest of the team. The goal was to build a proof of concept that we’d use internally.

The second chunk of engineering work was our push to get something live for customers by the end of the year: our first Minimum Viable Product (MVP). I worked as an individual contributor during this time, pulling tickets and shipping code.

My last major stint as an individual contributor writing code was in April 2020. This was peak COVID and the fundraising environment had effectively ground to a halt. So we had a discussion as a team to see where I could add the most value given that I had extra capacity, and we decided that my time would best be spent on engineering.

- Takeaway: Depending on where your company is in its lifecycle, you might find yourself doing individual contributor (IC) work. And that’s okay! Be humble and recognize that sometimes that’s where you can add the most value.

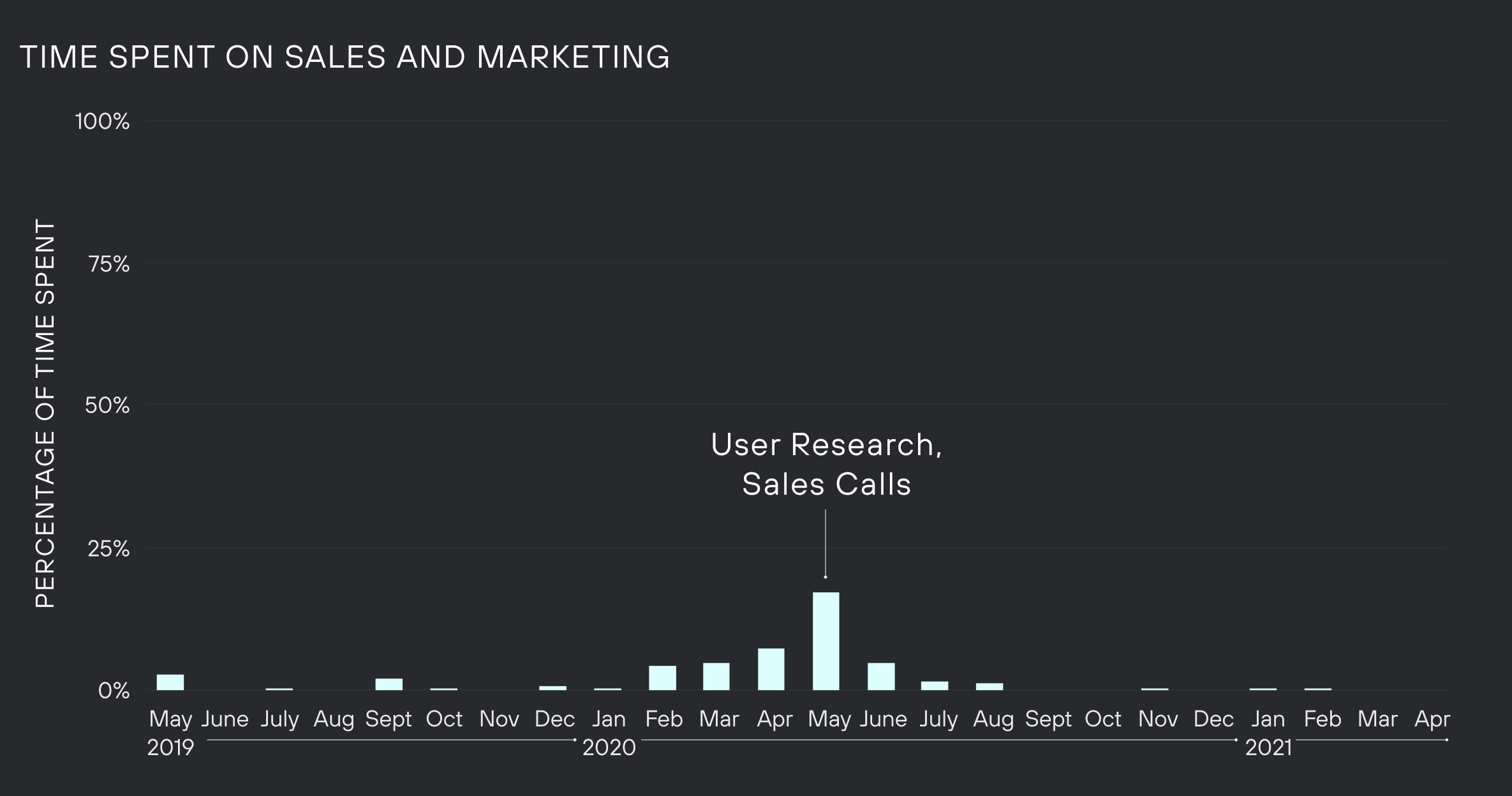

Sales and Marketing

Once we felt confident that we had a product people were interested in, we needed to get more customers and learn more about who they are and what motivated them.

We worked with a marketing contractor to put some basic ads together to get our first inbound waitlist signups and to start doing message testing. We spent ~$5000 over the course of several months to get the first batch of people to interview.

Every time someone signed up for the waitlist, they got a personal email from me asking if they’re free for a call. I received an email notification every time someone signed up and I manually sent an email to each prospect. Nothing was automated, and almost every person got a personal call from me in the early days — about 600, plus another 1000+ calls from the rest of the team. I started these efforts in February 2020 but really ramped up in May. There were weeks in May where I did 15-20 calls per day, each 30-minutes long.

There’s no shortcut here. The only way to learn who your customers are and deeply understand what problems you can solve for them is to hear their stories first-hand.

This was a huge time commitment, but the learnings from this time were vital for informing every aspect of our strategy. It was these conversations that led to the formation of our initial growth strategy, our product roadmap, and all other priorities within the company.

For example, it was in these conversations that we learned that most of our early members spent meaningful time listening to health and wellness podcasts and that they regularly use Google to search for health-related information. This is what led us to lean into podcasts — we’ve done 200 podcast appearances in the last 12 months — and content via SEO, because we knew that we would be able to reach the right kinds of customers through those channels.

- Takeaway: It’s critical for any CEO to deeply understand and empathize with their customers. The only way to do that is to put in the work and talk to them. Even though we’re two years in, I still do monthly calls with our members to get their first-hand experience. We call them “community calls” and it’s typically me and 6-8 members from our community for at least an hour. I listen to their experiences, their pain points, and I use it as an opportunity to float new ideas to see how they resonate with our members. Don’t underestimate how important it is to keep a pulse on how people are experiencing your product!

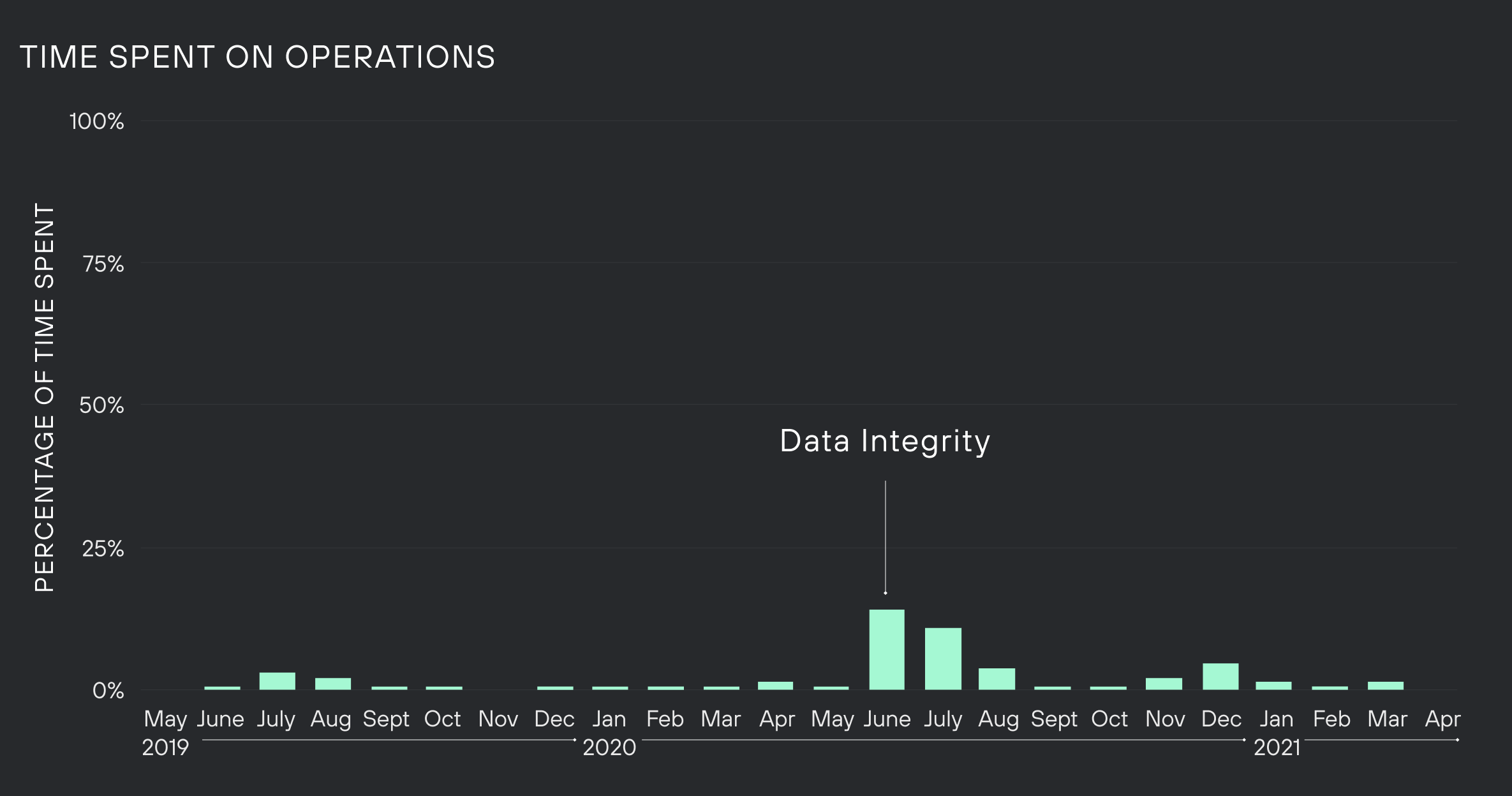

Operations

As an early-stage company (especially in the very early days), what we classify as operations is basically “anything that isn’t product or engineering.”

After the increase in order volume we experienced from the May 2020 sales push, we started to see cracks in the manual, spreadsheet-based system we implemented. We were dead reckoning between several disconnected systems and we had no source of truth for our data. We made this choice knowingly to get us through that phase (see Do Things that Don’t Scale), but it was starting to cause real problems, so we had to fix it.

Nobody else on the team had the bandwidth and context needed to take this on, so I jumped in. I manually processed, updated, and reconciled every customer record by hand, one at a time, across all platforms — there were on the order of 1,000 by this point. I built dashboards to shift our source of truth to our primary database and off of Google Sheets and other disparate sources.

- Takeaway #1: It’s okay to build systems that are not scalable in the early days. The goal is to learn what’s working and what’s not. Spreadsheets and Google Forms are great places to start. We didn’t have a proper database set up until a year after we started the company.

- Takeaway #2: As a startup CEO, you have to be good (but not necessarily great) at everything. It’s a huge asset to the company to be able to jump in and contribute to every part of the company.

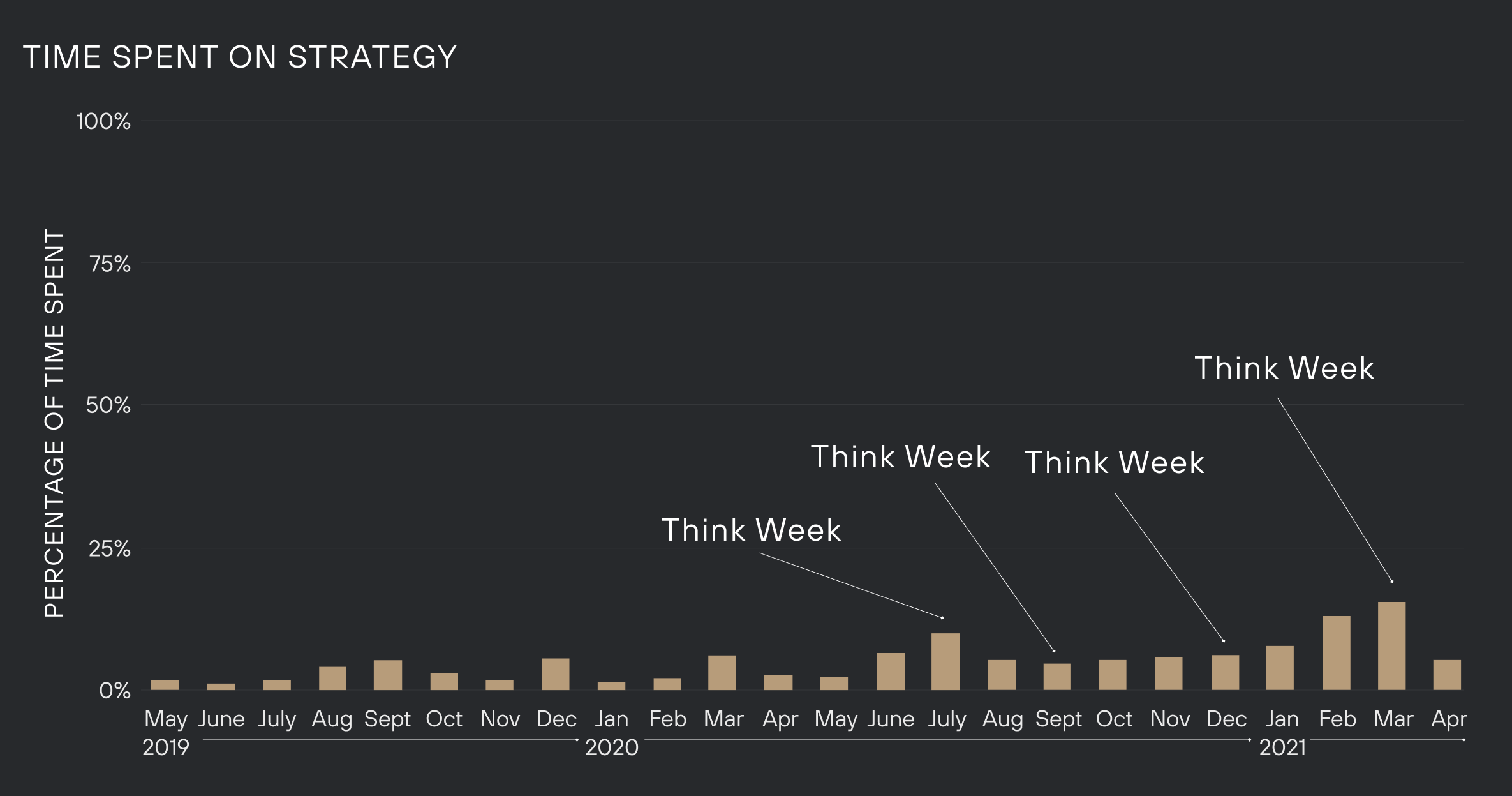

Strategy

We’re a memo culture, not a meeting culture, and we put a lot of time into long-form documentation. Why? My belief is that content scales; your time doesn’t. I’ve personally written many hundreds of pages of strategy and documentation to align the team. Keep in mind what content replaces: taking meetings to explain the same material over and over again, emailing people, meetings, calls, seemingly endless meetings…

Writing good documentation often takes a lot less time than you’d expect, and you don’t need to be a huge company to see the benefits of the information scalability that it enables — and the amount of your time that it frees up to work on more creative problems.

Given how core this is to our culture and how robust our documentation and knowledge management systems are, I was surprised to see just how little time I actually spent on strategy. This is one of those interesting cases where my perception of time spent is very different from actual time spent because doing this type of writing takes a lot of emotional energy. A 30-minute call with a team member feels like 30 minutes, but spending an hour writing a strategy document feels like it took the whole day.

One thing that I started doing in 2020 that’s been immensely helpful is a quarterly “Think Week” with my brother Chet. For Think Week, I don’t take any meetings or calls and just spend time thinking and writing. I’ve found that taking a Think Week is a great way to force me to take a step back from the day-to-day and think more holistically about company strategy.

Having done a few of these, here are some tips on how I do them effectively:

- Block off time in your calendar well in advance. I often block off the entire week on my calendar 2-3 months in advance.

- Bring other folks with you. I have a hard time staying motivated when I try to do Think Weeks by myself.

- Set expectations with the people you’re doing a Think Week with and let them know that there are no set schedules and that group dinners etc., are all optional. If you’re in a flow state, don't break out of it due to feelings of social obligation.

- Set an OOO reply for email, put your phone on airplane mode, use website blockers to block email, Slack, Twitter, or anything else you think might distract you. No calls, meetings, or expected communication during the week. I usually check emails each morning for <1 hour in case I need to unblock something, but then I turn it off for the rest of the day.

- Open a Google Doc and just start writing. The easiest way to overcome writer’s block is to just start writing. Oftentimes, my first drafts are a barely coherent jumble of sentence fragments. But I’ve found that if I just keep going, the thought itself almost always crystallizes into something useful.

It’s easy to miss the forest for the trees when you’re building a company. Taking some time off is a great way to gain a new perspective.

- Takeaway #1: You’re probably spending a lot less time on strategy than you think you are. If strategy is important to you (which it should be, as the CEO), you might want to consider reallocating your time to make strategy more of a priority.

- Takeaway #2: Writing out your strategy in long form not only has the benefit of forcing you to think deeply about your company, but it also has the bonus of gaining alignment from your team. To paraphrase a recent conversation with one of our new hires, “I feel like I know more about Levels and the team after working here for two weeks than I did at my last company after working there for five years.”

- Takeaway #3: Going largely offline for a Think Week is a great forcing function to think deeply about strategy and crank out a lot of written content.

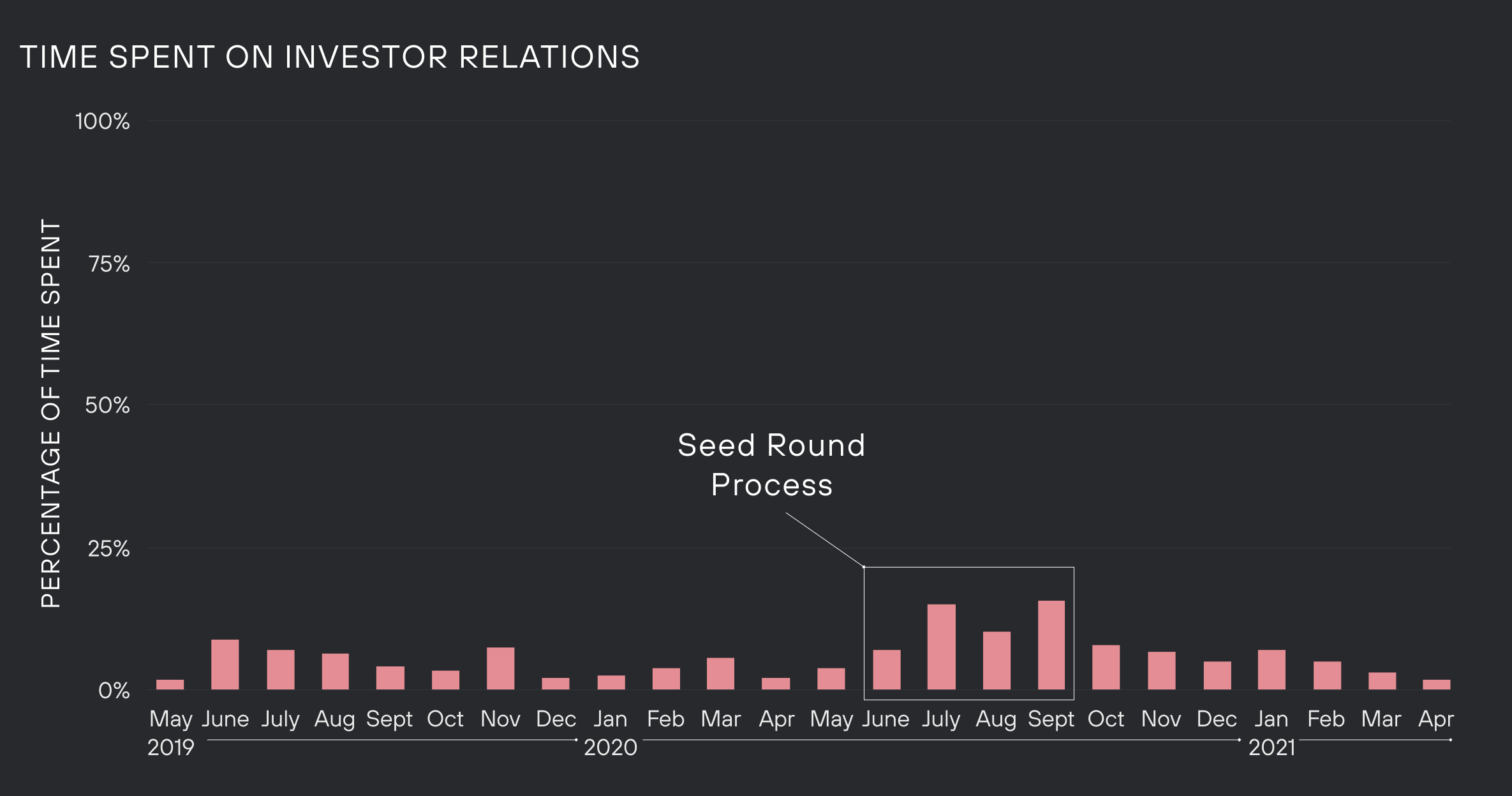

Investor Relations

We have five co-founders, but we agreed that because of my experience as a multi-time founder and for the time efficiency of the team that I would be the only one spending meaningful time on the fundraising process. It's not time-efficient to have all our co-founders involved — they have work to do!

I ended up spending less time on fundraising than I was expecting — especially during the peak of the fundraising process for our seed round — and it’s a lot less than I’ve seen other CEOs put into fundraising in their content pieces on time management. My theory is that most CEOs spend less time on fundraising than they think, but because it’s a stressful experience with a high emotional cost, it feels like more time is going into it.

It could also be because we put a lot more effort into writing down our thoughts and keeping our investors (and potential investors) up to date. We send out monthly investor updates to a select group of people, which gives them visibility into how we’re performing over time and reduces the need for synchronous “check-in” calls. As an example, we’ve made our Content Strategy doc public to give you a feel for the depth of thought that we put into the docs we share with investors.

- Takeaway: Use content to scale your time. Unless you enjoy taking calls to repeatedly answer questions like, “What’s the TAM?”, “What are the customer personas?” and “What’s your go-to-market strategy?” you should try to solve this by writing those ideas down and sharing the written content. I guarantee it will save you time in the fundraising process — and it has the added benefit of sharing context with everyone on your team!

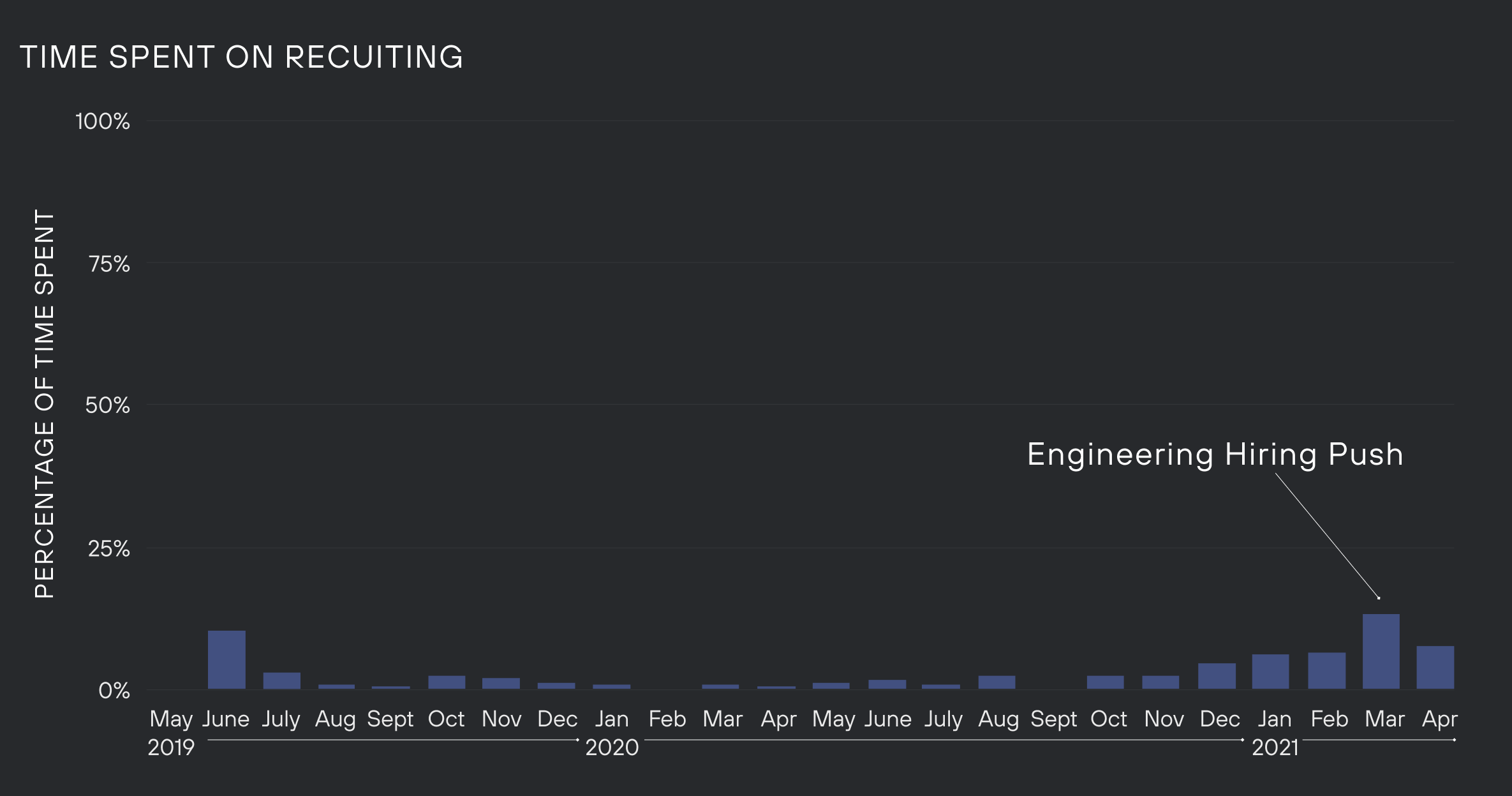

Recruiting

Time spent recruiting new team members was another head-scratcher for me. If I were to make a guess as to how much of my time was spent on recruiting, I would have said at least 20%, but the data tells a different story. In a typical month, I would spend less than 10 hours on recruiting new team members (or about 2 hours per week).

When I see charts of how other CEOs spend their time, the percentage of time spent on recruiting is usually much higher than this, which either means I’m spending less time on recruiting than is typical of a startup CEO (which I don’t think is the case), or it means that other CEOs are overestimating the amount of time they spend on recruiting.

Even during times when it felt like all I was doing was recruiting — like our engineering hiring push in March of 2021 — it was still never more than 14% of my time that month, and rarely more than 10%.

I started doing this analysis in February, and the lack of time committed to recruiting really stuck out to me. So I doubled down on recruiting in February and March to make sure we’re bringing in the best people. This is what the following months looked like:

- January - 38 calls, 49 outreach

- February - 34 calls, 423 outreach

- March - 60 calls, 623 outreach

And even with that huge push in March, it still only ended up at 14% of my time. Recruiting is hard!

- Takeaway: You’re probably spending a lot less time on recruiting than you think you are. If recruiting is a priority for you, it might be worth auditing your time to make sure you’re spending as much time on it as you think you are.

Team

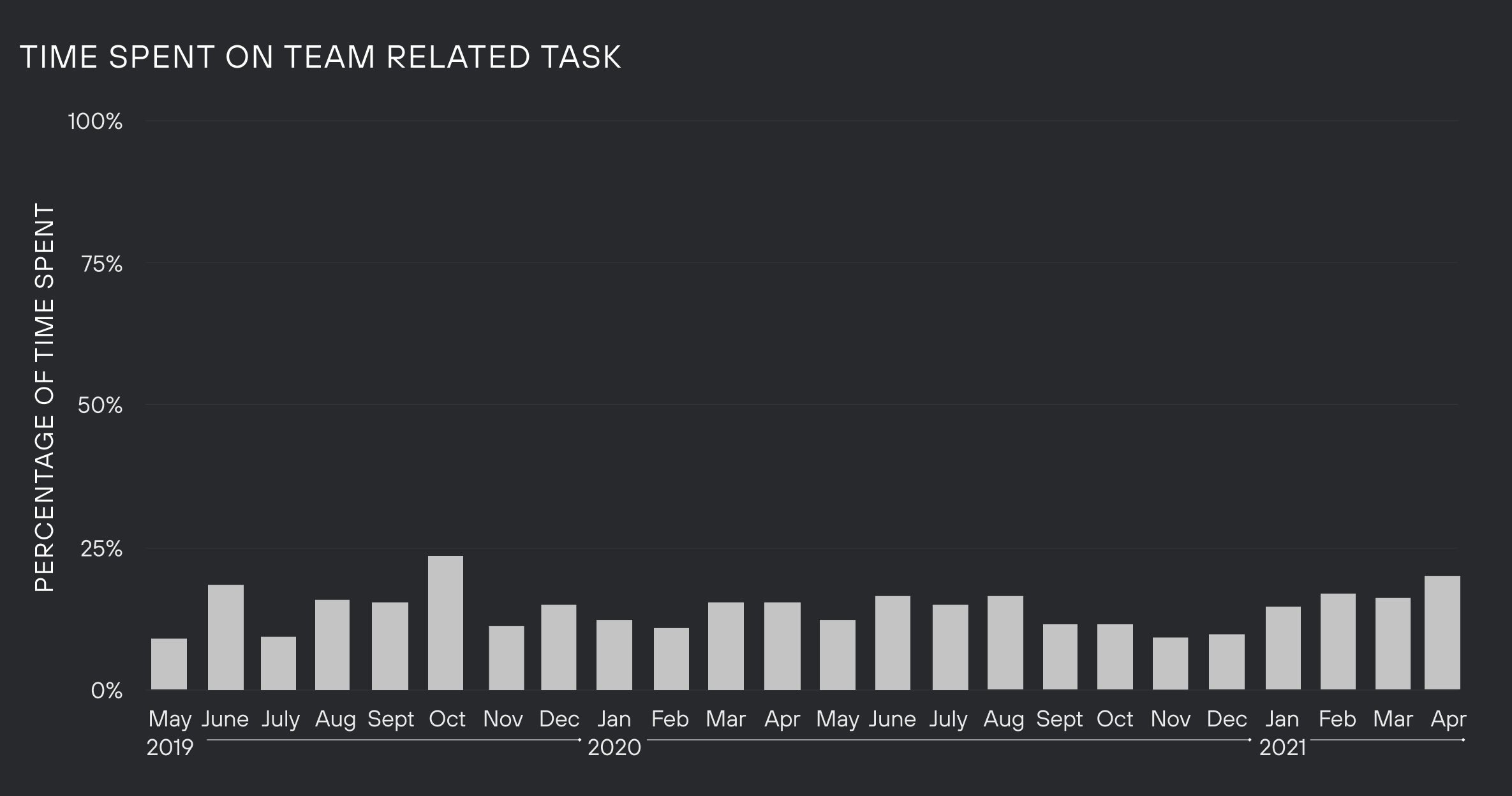

This category includes all meetings I was involved with that had at least one other person on the team included: things like 1:1s, company all hands, and team collaboration. What’s interesting about this data is how consistent it is. In June of 2019, there were only two people at the company: me and my co-founder Josh. And yet, I spent about the same amount of time on team-related tasks as I did two years later, even though our team was more than 10x bigger and I had many more direct reports.

I think one of the reasons why this is possible is that we’re diligent about getting rid of unnecessary meetings and, as a company culture, we’re highly skeptical of recurring meetings. We constantly reassess whether a given meeting is adding value, and we change things all the time depending on who is working on what project. At many companies, there’s an expectation that you need to have 1:1s with everyone you work with and that they need to be done weekly, but that’s not the case here — my co-founder Josh and I, for example, have 1:1s at most twice a month.

- Takeaway #1: Set the expectation that the cadence of meetings like 1:1s is subject to change as responsibilities change. I recommend revisiting all recurring meetings at least once per quarter. I’ve found it helpful to frame changes as an experiment to reduce the emotional cost. For example, “Let’s try changing our 1:1 cadence from once-a-week to every-other-week for a month and see if we notice any difference.”

- Takeaway #2: Never give updates in meetings — always lean towards asynchronous. This can be done either in writing (via email) or better yet as a video (we use Loom for screen recordings). You might be surprised how much better it is to do updates asynchronously via recorded content. An unexpected benefit of recording updates as content is that you can make them available to the whole team, or share them with external parties if they’re relevant, which saves everyone time.

Information Processing

This category includes a lot of things, but it’s mostly email. This also includes things like responding to Slack messages (although we don’t use Slack the same way most companies do), responding to Twitter DMs, and processing information from a number of other channels. But probably 90% of this time is email.

I highly recommend developing your skills related to email. Being good at email (and communication broadly) is a crucial skill for a CEO. Having spent countless hours on email, here are some of the things that I’ve learned:

- Be an “inbox 0” person. Use a tool like Superhuman to supercharge your ability to process email. I try to hit inbox 0 at least once a week.

- Use hotkeys for everything. When you process a lot of emails, saving a few seconds on every email adds up quickly. If you’re using your cursor to click on things, you should try to find the hotkey that does the same thing.

- Use snippets. If you find yourself sending the same information more than a couple of times, move it to a snippet. You can also create smaller snippets and compose longer emails with multiple snippets.

The chart below shows the average number of hours spent per week on information processing (mostly email) in a given month. For example, in the month of August 2020, I spent an average of 34 hours per week on information processing.

- Takeaway: Many CEOs treat email like a second-class citizen and squeeze it into their time between other tasks without recognizing how much pain it causes the rest of their team. Block off time specifically for communication.

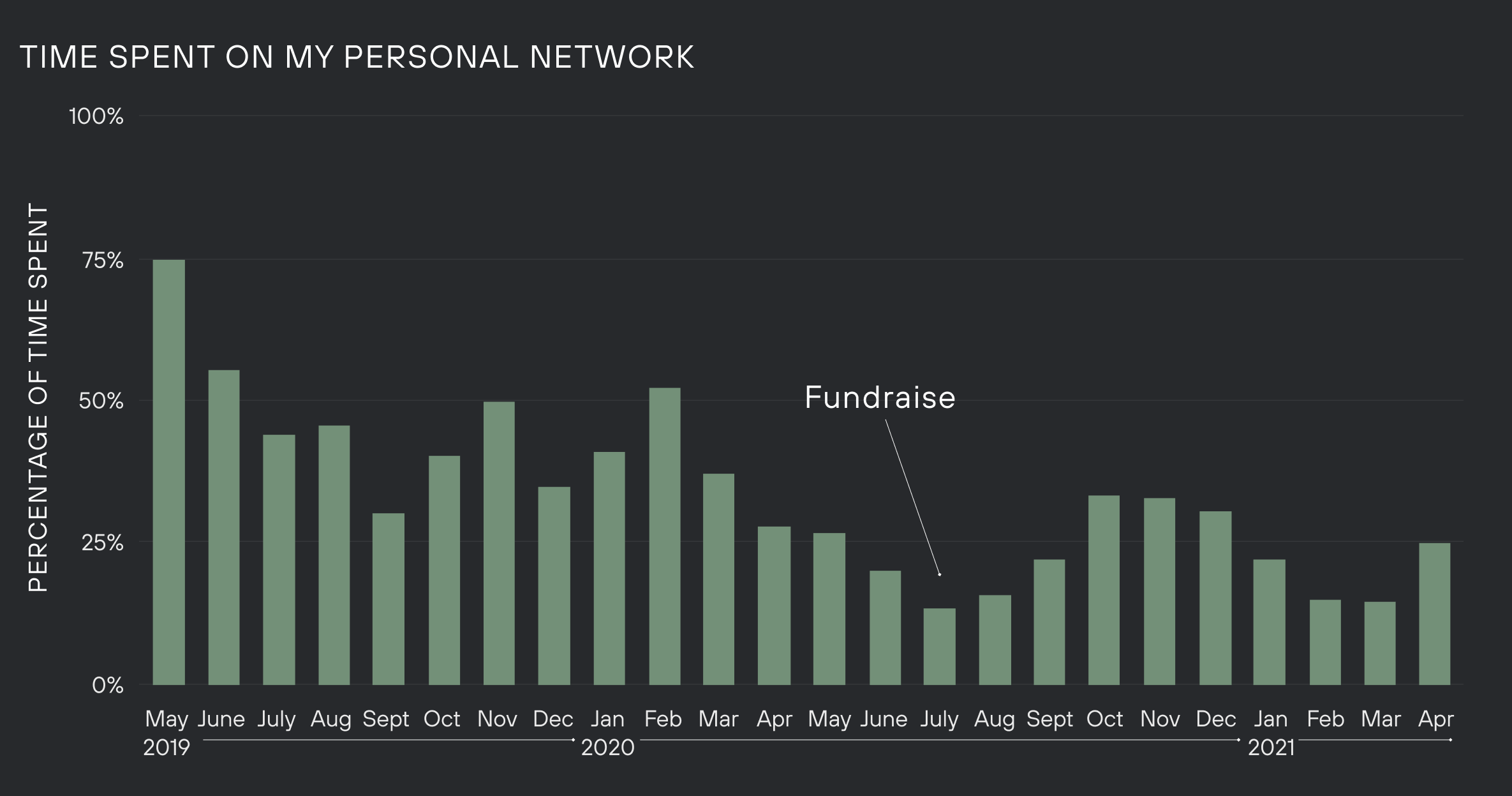

Network

And the last category is time spent managing my personal network. This includes everything from catching up with work-adjacent friends, meeting other people in similar or different industries, and generally learning as much as I can from the startup community.

Time spent on network maintenance took a dip during our fundraise, but it’s generally something that I spend a lot of time doing both because it provides a lot of company value, but also because it’s a major source of personal fulfillment. I have a quarterly goal of keeping in touch with 1,000 people. If you want to get better at cultivating your network, the best place to start is to just keep a list. The system I use for myself is very similar to the system that Peter Boyce uses in Airtable — don’t overcomplicate it.

These calls, events, and meetings often end up covering a lot of ground and can transition into investor relations, team, recruiting, etc. over time. Many of the calls that were categorized as investor relations in July started out as networking.

- Takeaway #1: Having a strong network is a critical piece of being a startup CEO, and being good at following up and asking for the right things from the right people is a superpower. Be respectful of other people’s time, and be organized. I follow up with close to 100% of the people I talk to, and I send an email to the person who made the introduction thanking them for making the connection. Make time for follow-ups — very few people do and it makes a huge difference.

- Takeaway #2: Always have a list of “asks” ready. At the end of a lot of meetings, people will ask you, “How can I be helpful?” and most of them genuinely want to help. Personally, I’m terrible at coming up with these things on the spot, so having a list of asks in my back pocket makes a huge difference. Some of the most important, serendipitous events in company history came from being prepared to answer the question, “How can I be helpful?”

WRAPPING UP: TIPS FOR GETTING STARTED

If you’ve made it this far, you’re probably the kind of person who wants to know how to do this yourself. Here are some tactical steps you can take. The first thing you need to do is create the categories that make sense for you and your business (but remember — no more than 10!), keep a rigorous calendar and back-fill how you used your time on a given day. If you want to back-fill with your existing calendar data, you can go into Google Calendar and download all your historic calendar data as a CSV, then upload it to Google Sheets. If you haven’t been keeping a rigorous calendar to date, you’re better off starting fresh and keeping the spreadsheet up to date going forward.

I created a (simplified) version of the spreadsheet that I use myself, which you can make a copy and use for yourself.

It may seem like a big undertaking at first — but the investment up front to set up the system (and regularly maintain it) will buoy your effectiveness and impact as CEO for years to come.

Image by Getty Images / MirageC

Chart illustrations by Jeffrey Chan